click on image for larger view

Punk Posers On

Parade

Since the 1950s, Capitalists have had a big interest in the philosophy of the

market. Business theory has always followed trends, as that's where the money

is. A healthy cynic might say: consumerism, like a parasite, corrupts the trends

it syphons off of.

In 1959, Norman Mailer published his omnibus collection Advertisements For

Myself. Its section "Beat, The Christmas Tree of Hip" warned that

cooptation and commodification where the biggest threats to the counterculture.

Those in "the underground" toked on their cigarettes, and laughed.

Behind their backs, Madison Avenue plotted, many thanks to business manuals,

such as 1960's The Human Side of Enterprise by Douglas McGregor, which

proposed "Theory Y": think outside the box, or vanish underfoot of

those scrambling towards the future.

Plenty of business theory began to find its way into politics, culminating in

1968, when C.I.A. member Richard Helms wrote a report for Henry Kissinger, titled

"Restless Youth", outlining ways to steer kids into becoming better

citizens. In those days, governments learned that when revolutionaries roam

the streets, their greatest defense against them was to homogenize their revolution

- best done by cleaning up the music, as well as said streets.

It makes sense when one follows the rise and fall of rock in the late 60s, punk

and hip-hop in the late 70s (and again in the early 90s), as well as metal in

the early '00s - four times extreme political expression found its way into

music, and was nullified.

In the late 60s, the record label rush may have helped spur activism when it

came to the war, but it actually toned down the revolutionary rhetoric of many

of the artists. Even more dissent was taken out of rock, as the neighborhoods

- which spawned these bands, and radicals - became gentrified beyond their expense,

causing a diaspora of hippiedom. Who wants to party when your scene's been decentralized,

and the music's watered down?

Labels knew they

could make a dollar off of anything "revolutionary", and they didn't

mind to remanufacture something until it was turned into a caricature.

It all suited Big

Business, as whatever helps the consumer class grow is, to them, a good idea.

Later, when punk politics began to become a threat to the established upper

classes, its ideals needed to be taken down a notch.

There are two ways to water down a message, and both use misdirection. Political

use of these two concepts stem as far back as the 1920s through the fields of

public relations, pioneered by nephew of Sigmund Freud, Edward Bernays, and

Gustav LeBon's crowd control studies. On one path the point of interest being

driven toward is sex, the other is toward death; Eros and Thanatos.

When used positively these forces embody love, and the building of civilization

in respect to death, but negatively they represent the act of lust, and violence

due to a fear of death.

What Private Enterprise had learned in the late 60s was put to good use when

punk rock reared its ugly head.

A lot of (even the art school of the first wave of) punk in mid-1970 New York

City was about lower-to-working class struggles. Many, especially the English

on the dole, took that message to heart. Kids began to preach Anarchism, or

- at least - a serious reevaluation of the current political model. By the time

many labels took notice, punk had morphed into hardcore; with it came a greater

anger, with the knees of those in power beginning to shake, and not from the

volume of the speakers.

Record companies wanted to buy into "the punk thing", and in many

cases the behavior of artists they picked up were corralled well enough. By

the time punk became political, the record companies' shopping spree into the

sellable sound dried out. When they couldn't sign new "wholesome"

acts, they convinced bar rock bands to take on the punk look, and when they

couldn't finds bands to do so, often just made up new ones.

One such example is the 1977 LP by Christ Child, which was put out - wouldn't

you know it? - by Buddah Records (an arm of MGM, which turned psychedelic protest

rock into bubblegum pop).

Christ Child was started by studio musician, and production manager, Richard

"Daddy Dewdrop" Monda. The label offered him a release, and - after

a session musician went from a Zydeco recording to a heavy metal one, telling

him "Notes is notes," - he then realized to play whatever was popular

at the time.

With a bland punk

sound, and phony attitude plastered all over the album's sleeve, the lyrical

content is blushingly bad, and almost always about sex.

Not to be confused with the '77 Belgian band with a 7" on Romantik Records,

the U.S. also had a Chainsaw 7" released upon them the following year by

a Los Angeles record label calling itself C.I.A. Records.

Complete with punk

look, phony sound, and a misspelling of the title track, it was - thankfully

- Chainsaw's, and C.I.A.'s , only release, but I'm sure other nefarious things

came from those two camps (though this trash has currently been rereleased on

CD with extra tracks, and a Stooges cover).

Another counterfeit outfit were across the ocean: The Depressions from the UK.

Originally called Tonge, they were a Who cover band from Brighton.

Approached by Animals'

bassist, Slade manager, and hit-single factory Chas Chandler, they withered

back their roots, and sprouted new leaves as a punk foursome (complete with

an eye-patch for the drummer on the cover of their self-titled 1978 LP). As

usual, the lyrics were a far cry from punk, and wailed about fashion accessories

instead of electioneering. Many of the concepts behind the building of The Depressions

were the exact same that propped up - my, not only favorite fake-punks, but

favorite band of all time - The Police, but it didn't work in The Depressions'

favor.

Every section of the world that was touched by punk, was followed by pose. Even

Europe had fakes, like Flyin' Spiderz. This Dutch act was led by singer/songwriter

Guus Boers, and backed by EMI. They suffered from the usual banal lyrics that

many fake punk bands can't help but to sing about (one song is a serious complaint

about loud groupies).

Some labels didn't

even make up music acts, instead giving "punk songs" to already existing

boy bands, such as Germany's The Teens, who were complete with a leather-jacket-wearing

bad boy.

Or when The Village

People's movie flopped, and knowing disco was dead, tried their hand at punk

on 1981's Renaissance.

The sad truth is

that consumerism redefined as revolution becomes a cartoon, and that's what

punk became to many.

Even sadder than

corporate cooptation is when misinformation becomes the only publically-disseminated

information. You'll know when the Free Market has succeeded, because calumny

will rule. Case in point were the many bands that popped up throughout the 80s

based on their poor interpretation of punk, and, wanting their act to be outrageous,

stuck with it.

One of the many great examples is Puke Spit and Guts' 1980 LP Eat Hot Lead.

This group of L.A.

bar bikers didn't need a label telling them what to do, thinking it best to

jump genres themselves, and though now a collector's item, the output has become

a tangible cautionary tale of cultural homogeneity.

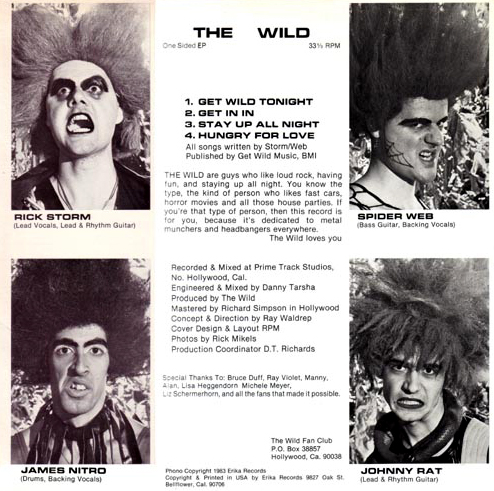

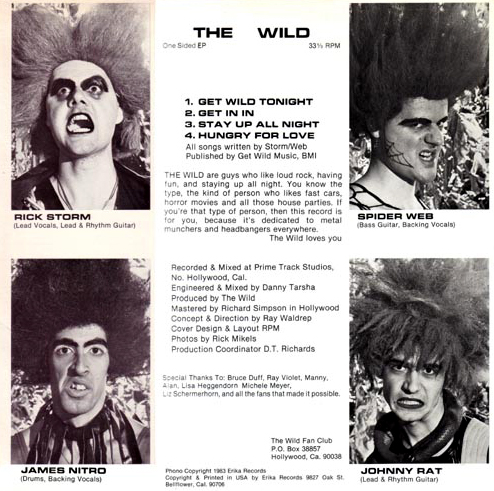

The worst-case-scenario in this faux pas of musical paths would have to be The

Wild.

In 1983, Erika

Records - which was not a record label, but a record pressing plant - thought

to cash in quite late on a music phenomena, and put together one of the most

embarrassing picture discs to ever be shelved in a record store's punk section.

click on image for

larger view

There are a few

who might think this is all in fun, and much of it may have been, but there

is a serious disconnect between the original idea, and what it all soon became.

I get that if this commodification didn't exist in the scene we wouldn't be

able to enjoy much of the nostalgia we suffer through today, as Rhino Records

not only does well on rereleasing forgotten gems, they also began to make a

living off the circulation of this drivel to begin with. Their third release,

1978's Saturday Night Pogo: A Collection of L.A. New Wave Bands, was

a compilation, which mixed actual punks like The Dils, and glam outfits like

Daddy Maxfield, while packed full of phonies such as The Motels (known as The

Warfield Foxes, they moved to L.A., and changed their name along with their

sound), as well as the previously mentioned Chainsaw.

But take away that

cathartic blast from the past, and you're left with what's really depressing:

dead dreams. Though we may caution, it keeps happening.

In the late-80s, when hip-hop became a battle call for the uprising of urban

youth, much of the enlightened rage of Public Enemy and Eric B & Rakim were

diffused by the Thanatos-loving gangster ethics of NWA and Ice T. When it resurfaced

in the early 2000s in poor white neighborhoods through metal, the opposition

already had Eros-preaching assholes standing in line with the likes of Crazy

Town and Linkin Park, calling it nümetal.

If we can cling to one shard of hope in this broken pile of prospects, it's

that revolution is possible, because they are afraid of it. Work hard at it,

but don't voice your complaints too loudly. Like a pest, if they hear you, they'll

try squash you (or maybe just buy you out).

A. Souto, 2016

BACK TO MUSICA OBSCURA ARTICLE LIST