OCCULT INFLUENCES IN PHOTOGRAPHY

This

is a rewrite of a lecture, originally given in the class Projects in Photography,

at

NYU's Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development's

Department of Art and Art Professions, on Feb 20th 2013.

INTRO

Photography has for many seemed to be linked with magic, and there are still

parts of the world where people can hardly believe the photographic technique

is real.

There is the mythical link between the lens and the occultists' All Seeing Eye,

especially amongst conspiracy theorists.

In the study of

optics, some Greek philosophers believed in lenses that connected the world

of gods and humans, and when one knows how to adjust their sight, can view the

gods, and the gods looking back at us.

There is constant reference to photos holding magic.

While photography seems like magic, they come from two different spheres of

performance studies, as well as theory. The metaphor "photography as

magic" by the time it reaches the ears of a fourth or fifth party has become

"photography is magic", but one is temporal, while the other

is hallowed.

The art and process of magic is to create a moment, using one's will to reach

out into the physical world, always moving, and affect as many people as possible.

While photography is the opposite. It's a means which captures a moment, keeping

it static. Yet, when the process is artistic, it is also done to affect as many

people as possible.

Still, ritual and photography are symbolic, and both invoke complex associations

through the use of simple objects.

In the late 70s, the foundations were set for the school of Ritual studies,

being a mix of anthropology, performance study, and the study of religion and

myth, which is ethnographic in nature, and draws heavily from the work of an

eyewitness.

Deeper, we become bogged down in philosophy, and as the lines between macro

and micro thins, we cannot help but to get into theories on the observer, and

their possible effect on the behavior of a system.

The Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, and its mind-body problem,

states that we have an effect on reality by simple observation. Schrodinger's

theoretical cat is just as artistic as it is mystical. As Nietzsche wrote, "We

are all greater artists than we realize."

Accordingly, there has always been magic in photography.

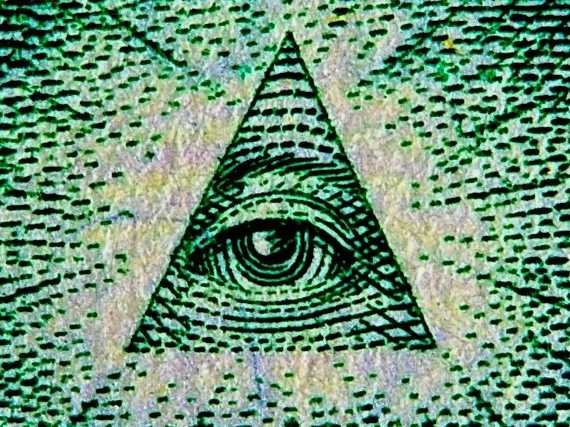

PROTO-SCIENCE: ALCHEMY

Alchemy and chemistry are two brothers who constantly learned from one another.

The fact is that

one would not have evolved without the help of its near-equal. If not for alchemy

mankind would never have had chemical and spagyric plant processes, including

gun powder, and hence photography.

Alchemy is commonly known as the tradition of mixing chemicals with ritual to

obtain what is called the Philosopher's Stone. May argue that it is either a

way of turning base metals into noble metals such as gold, or an elixir of immortality.

Even though alchemy and chemistry are over 5000 years old, neither was deemed

an exact science until the middle ages. Alchemist Robert Boyle, known for his

studies of gases, is often thought of as the godfather of modern chemistry,

and it is known that Isaac Newton received his inspiration for the laws of gravity

from studies in alchemy.

Along with the alchemic process came the processes for developing photographs,

the invention of film, the creation of plastics, etc.

THE BEGINNING:

OCCULT ORDERS

Around the late

19th Century, we have the rise of both the occult order, and the use of photography.

Westerners were setting up lodges and occult groups, structurally and dogmatically

based around Freemasonry, such as MacGregor Mathers' Hermetic Order of the Golden

Dawn, Carl Kellner and later Aliester Crowley's Order of the Oriental Templars

also known as the OTO, Helena Blavatsky's Theosophical Society, etc.

Magic is split up into several categories. You have stage magic - sleight of

hand - and you have magick (spelled ending with a K), which itself is split

into two schools: lesser magick is the use of energies to bend space/time in

one's favor, while ceremonial magick is used to better the entire structure

of the Great Architect's universe through one's personal experience and practice.

Occult, meaning: hidden, and secret societies were what they claimed to be:

secretive. Therefore there is no evidence of the use of photography in ritual,

or even to document ritual. Outside of documenting lodge membership,

or much later in the orders' histories, documenting postures and poses,

even ritual rooms.

The Westerner's

use of photography seemed to be limited to documentation for occult lodges,

but not practices.

Today, we commonly reach for cameras to document the rituals in our lives, but,

truth is, most ritual is not meant to be documented at all.

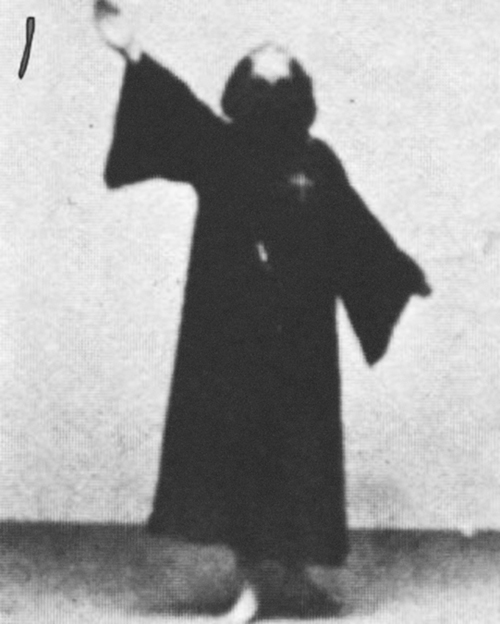

PHOTOS IN RITUAL

Admittedly, photography

presents more of an opening to ritualize, but not to a rite itself.

It may capture a moment in a ritual, but never the full aspect of a ritual.

Still, a photograph is thought to hold magic.

Around the late 1800s, Westerners saw lesser magic as common witchery, which

was primitive and beneath them, so the first to use photography in a ritualistic

manner were those involved in primitivist, animistic religions such as Voodoo,

or several forms of shamanism, where the belief is held that a photo can contain

someone's soul. They reason, a person can be helped or struck down by the use

of their image, whether through magic spell using a photograph, to simple damage

done to a photo. Spells of a beneficial nature can also be performed on a subject,

who may be many miles away, through their photograph.

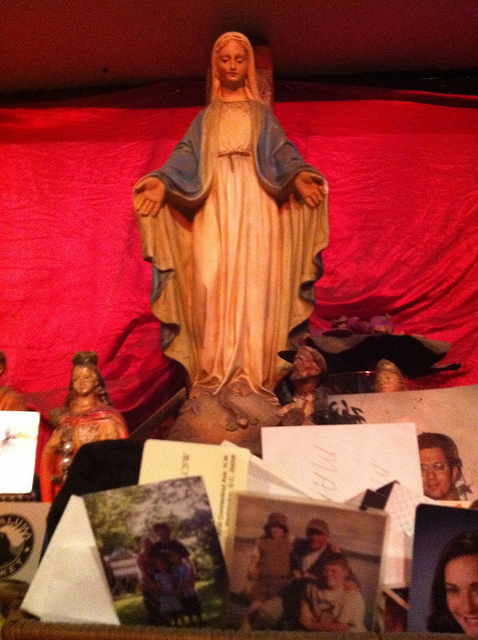

The image below is of benevolent witchcraft to heal someone using photographs.

Much of these practices are still used today in many religions throughout the globe.

CAPTURING THE MAGIC

Some artists found

fun in the macabre, while others heard a call from the other side, and produced

works with an occult air, but not necessarily occult themselves.

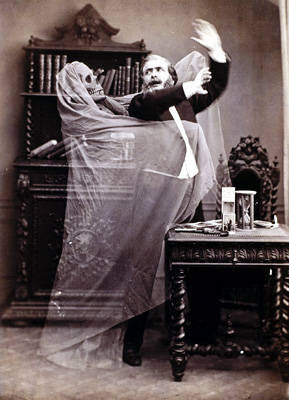

In the next two images we have playful yet morbid Albumen silver prints, respectively,

from 1860 by Eugène Thiébault, and 1890 by an unknown French artist.

As the Western

world's Fin de siècle worldview came to an end, 1900 - 1930, the

widest use of photography in an occult manner would be in attempting to capture

the supernatural world; from mediumistic practices, like séances, to

ghosts, and other unexplainable phenomenon, including trying to prove the soul

exists, such as spirit photography, pioneered by American William H. Mumler.

This image was taken by German psychologist Albert von Schrenck-Notzing in his

study of psychics.

Today, many of the photographs are proven to be somehow faked, and are deemed worthless to science, but still obtain an artistic value. A rare showing of many of these images coalesced as the exhibit, and its companion catalogue, The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult, which was held at New York City's Metropolitan Museum of Art, in 2005.

AD HOUSE NAZIS

Not long after

we have occult methods used in photography; not for ritualistic purposes, but

to sell something, from products to ideologies.

The photographer frames a shot, following inner artistic drives, most likely

in an empathetic expression, so as to have you feel what they feel.

Around this time, ad agencies began to use the camera to fabricate moments,

often ones that rarely exist in the real world, following outside instructions,

all to make one feel whatever emotion is necessary to sell the product. Their

power was not in argument, but simple suggestion.

Now, as alchemy spawned chemistry, the hermetic orders of western occult magic

helped bring about an interest in the mind, and psychology. Later psychology

gave rise to psychological warfare and propaganda studies. Edward Bernays, a

nephew of Sigmund Freud, known as the godfather of public relations is proof

positive of the link between them.

In 1919, he opened his first public relations office in NY, and taught courses

on the subject beginning in 1923. Many of his ideas are based on the works of

Gustave LeBon, who studied crowd control.

Another group who used much of what was put forth by LeBon, even Bernays and

Freud, was the National Socialist Party of Nazi Germany. Using set, setting,

color, syntax and even obfuscation, the Nazis manhandled all forms of art and

photography to create a form of hidden propaganda, all meant to manipulate the

inner workings of what they considered the Aryan mind.

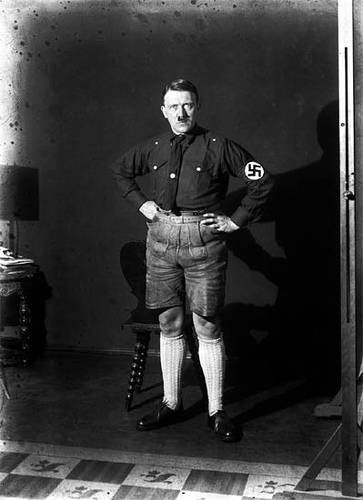

As an example of obfuscation, taken from the 1996 film The Empty Mirror,

we have a famous picture of Adolf Hitler, where he looks rather proud, used

in political posters to portray someone who is stern, and not afraid to heroically

pull Germany out of the clutches of her enemies.

Yet, pull back

to reveal where the image was cropped from, and if used on a political poster,

would have been laughable.

If anyone wonders

how much the Nazi party involved the occult in their works, all they have to

do is watch Leni Riefenstahl's Triumph of the Will to see how much magic,

both lesser and greater, is used in one simple propaganda film.

Currently, in much of advertising, photography is used to show a world you're

not currently in, but if you use their product, your life could change for the

better.

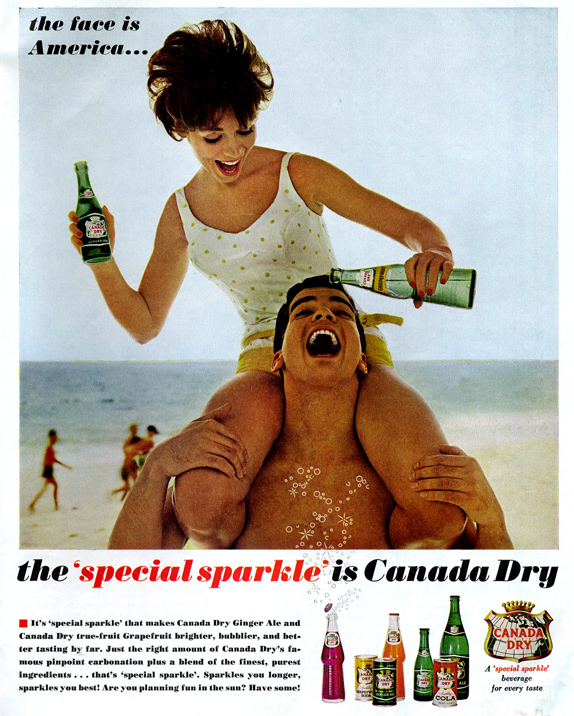

Most know this image has nothing to do with soda, but it shows a joyful world

you're not a part of, and may want to be.

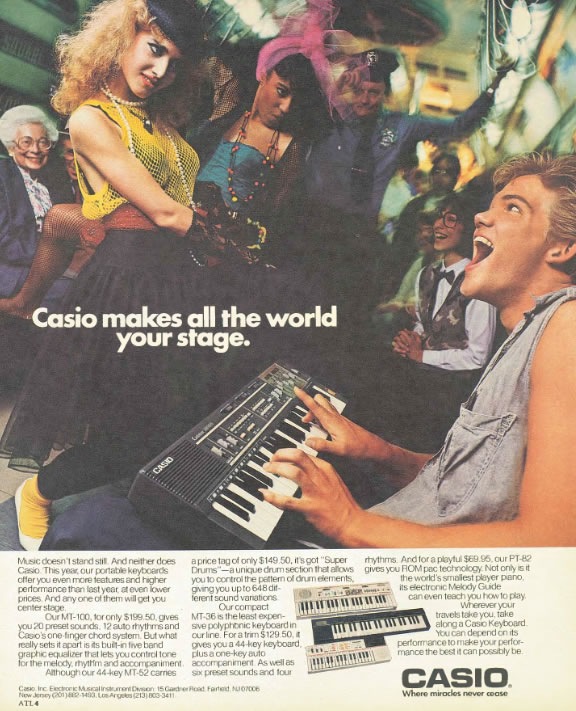

The next one shows how you can create that happiness, or attention you seek, with the use of their product.

Like a sci-fi novel,

or a tv show, the advertising image is meant to take you away from the state

you're in, and, in a split second, make you want to exchange where you're at,

to what is happening in the image.

Cultural anthropologist Victor Turner thinks ritual and advertising temporarily

dissolve social hierarchies, and momentarily reshape personal identity.

According to Michael Schudson, in his book Advertising the Uneasy Persuasion,

advertising is hyper-ritualistic in a capitalist realist system, and points

to the manipulation of ideals as the connection between advertising and ritual.

Since the modern age, both politics and commerce use near-magic, trance-like

states to push an idea, hypnotism and mesmerism. Like magic, their will sent

out to create change in time / space. The two schools of thought have practically

turned it into a war between information and confirmation, between those who

seek knowledge and those who are just looking for affirmation.

RITUAL IN PHOTOS

Like advertising,

Surrealist art was to work on the unconscious as much as the conscious mind.

Strangely enough, though they dealt in dream states, Surrealists did not use

the camera in a magic or ritualistic manner. While many did perform ritualistic

acts of performance art, and many artists used ritual in their material artwork,

the camera itself served little more than to document the act.

Avant-guard filmmaker Maya Deren shot 18,000 feet of Voodoo ritual footage,

and heavily documented possessions, rites and altars in both photo and film,

from the late 40s to the mid 50s.

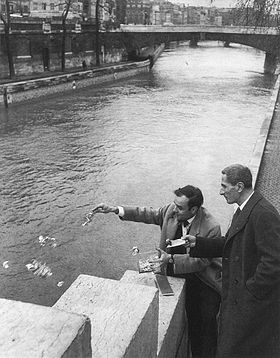

In the next image,

we see Nouveau Realist Yves Klein in what he called a ritual transfer of immateriality,

where he would, in exchange for gold, perform a ritual, and labeling it an invisible

work.

I found it odd

that I could not track down a single reference to Man Ray or Jean Cocteau using

photography as ritual, though a bit of the fore and much of the latter were

influenced by the occult, and the latter's film work was, admitted by the director,

to be quite occult in nature.

Vilém Reichmann in Czechoslovakia and Clarence John Laughlin in New Orleans,

Louisiana were two Surrealist photographers which heavily mixed occult themes

into their work, but neither mixed ritual and their art.

These acts constitute what Erving Goffman described as the "interaction

ritual", where ritual-like behavior lacks recognition of a formal rite,

more art than austere.

Many can argue that the Dada and Surrealist process of placing poetry atop of

photos, or the act of collage is a ritualistic process, but if the artist had

a magical purpose in mind, it went unsaid. The work may seem ritualistic, but

only in a mechanical sense, certainly not in a spiritual sense. And, while Joseph

Campbell claims that none are closer to experiencing what it's like to be god

than the artist in the process of creation, much of that is experienced in hindsight,

as the innovative impulse stems from inspirational urges and ideas many artist

don't even understand at the time.

Around the time of the Beat Generation, the late 1940s, artist stopped seeing

themselves as part of the nobility and academia, and more a part of the proletariat.

Artists were rarely beneficiaries of the state, and hadn't held court with kings

since the Renaissance. Artisans now saw themselves as laypersons, even street

people. With that came a reconnect with the lower class, mainly America's immigrant

and black population, coming with it shamanistic beliefs, and the practice of

witchcraft.

Soon after, Brion Gysin, many times under collaboration with Ian Sommerville

and William Burroughs, was possibly the first to introduce photography into

ritual, using the camera's eye to capture a moment as well as create one.

Many times Gysin would look out the windows of his flats in Paris and Morocco,

and with an idea to manifest, or wishful thinking, took a photograph from his

particular vantage point. He would then ritualistically paint, write or color

the photographic image, and place it back on the window, so as to replace the

mundane viewpoint with his more magical perspective.

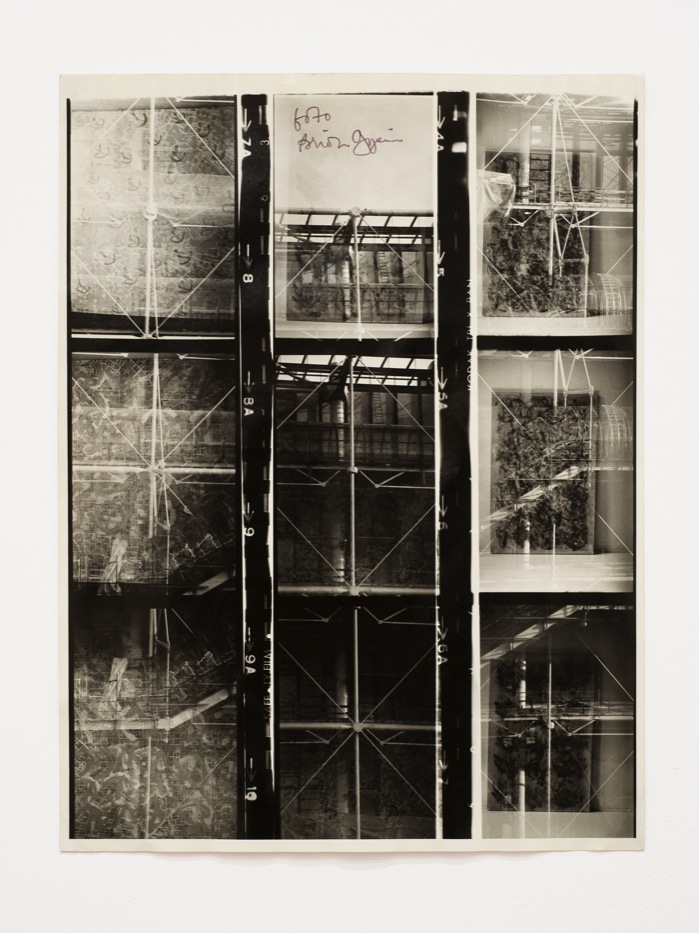

This image shows a collage, seminal of his later grid-worked pieces, of his

view from their last Paris hotel room, which became best known as "the

Beat Hotel". All they saw was the Beaubourg facade next door, but many

of the images where meant to affect locations and have influence further beyond

what they could see.

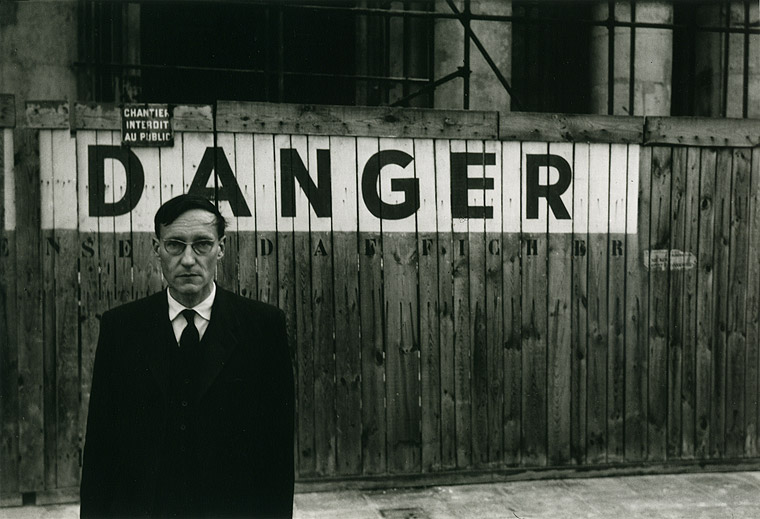

The following image

comes from the "Danger series" Gysin took of William Burroughs. Both

wanted Williams' new novel, Naked Lunch, to succeed, but with a modicum

of infamy, notoriety and even wickedness. The magic spell, while as a result

were used as publicity shots, were a ritual to put all of this in motion in

the world of literature, not to mention an advertising move to market Burroughs

as, of course, dangerous.

The method of writing

the aforementioned book, which Gysin originally came up with, was a ritualistic

practice of Dada-esque poetry - using scissors and replacing old text with new

- and while the rarely had anything to do with photography and film, they did

lead to Antony Balch's films (Towers Open Fire and The Cut-Ups),

with William Burroughs, in the 1960s.

Much of this inspired the works of current filmmakers, including Kenneth Anger,

Alejandro Jodorowsky's El Topo and The Holy Mountain, Fluxus filmographer

Nam June Paik's meditative Video Buddha, later, the later works of Jan

Svankmjer, and even the Quay Brothers.

THE MODS

Photography and

magic have never been so entwined as today.

In their private lives, thousands of people currently use the camera as a ritual

tool; in lesser magic to help or hurt, all the way to self-reflective greater

works meant to uplift mankind's spirit, or just challenge and ask the question,

"When does the artistic process truly end?"

Hundreds of others openly mix magic and photography in their artistic fields.

In 2000, author and anthropologist Ronald Grimes taught a course called "Zen

Meditation, Zen Art" where he ask his students to take "Zen photographs",

the ritual act of taking pictures without thinking of taking pictures.

Photographer Mellissae Lucia, from New Mexico, who also studies shamanistic

practices around the world, for years performed a private, ritualistic series

of self-portraits, titled The Painted Body, after the death of her husband.

Lucia states that the series was to help her come to grips with who she truly

was, more so than an artistic project. The project lasted seven years, where

she then made them public, and later released the work as a deck of tarot cards.

This photograph is titled Conduit, and is from that series.

Lastly, I would

like to share with you some of my ritualistic photography.

In March of 2012, after a 28 day, Lent-like ritual of fasting and self-denial,

meant to coincide with the phases of the moon and menstruation, I realized I

did not use my digital camera at all, except for video capabilities, so every

weekend, I took a one-hour walk through my neighborhood, and snapped a different

series of photographs each week.

I began the entire work using one broken camera, where I shot the sun behind

trees on a walk to break a fast. Upon returning home, I immediately threw out

the camera, which produced eight photos from this experiment.

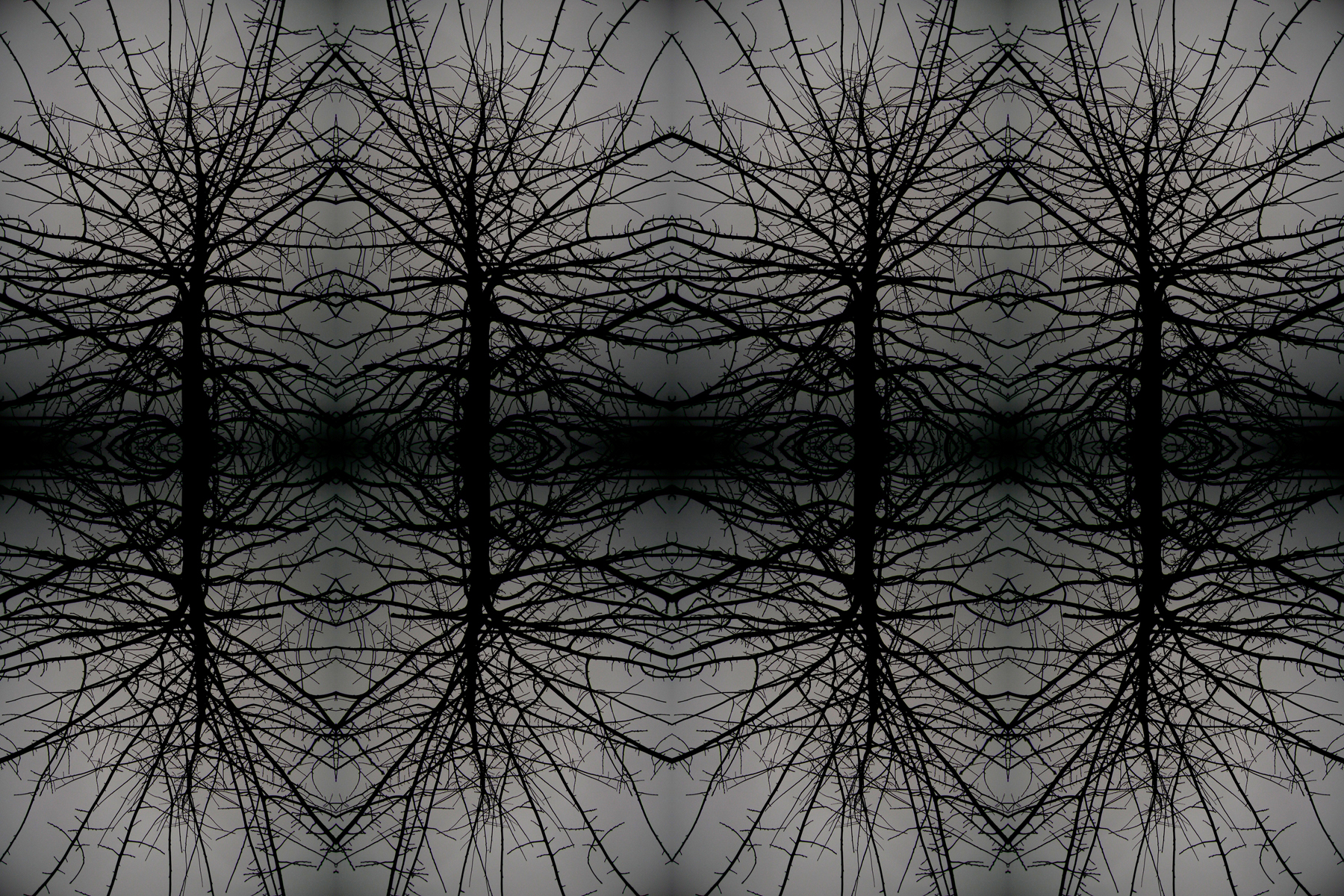

In March of 2013,

after ending a similar ritual, I took the previous photographs, and after flipping

a copy, produced several fractal patters. The more photos are added, even adding

in opposing schemes, the layout produces a bevy of never ending patterns. This

image, taken from photograph one of the 2012 series, is titled Crown of Thorns.

Finally, I'd like to show a short film of mine from 2009, titled A Female Sacrifice, filmed and edited simply as a ritual to help me quit smoking. I had no cameras of my own at the time, and used the tools that were available to me (a simple flip phone), proving one can not only find, but create, art and magic anywhere and everywhere.

CREDITS

The Perfect

Medium: Photography and the Occult, Clement Cheroux, Pierre Apraxine, Andreas

Fischer and Denis Canguilhem, 2005 (Yale University Press)

Rite Out of

Place: Ritual, Media, and the Arts, Ronald L. Grimes, 2006 (Oxford University

Press)

Ritual, Media

and Conflict, Ronald L. Grimes and Eric Venbrux, 2011 (Oxford University

Press)

Thanks to Delia

Gonzalez, Anthony Mangicapra, and Vanessa Sinclair for their help in this project.